The Truth About Our “Little Brain”

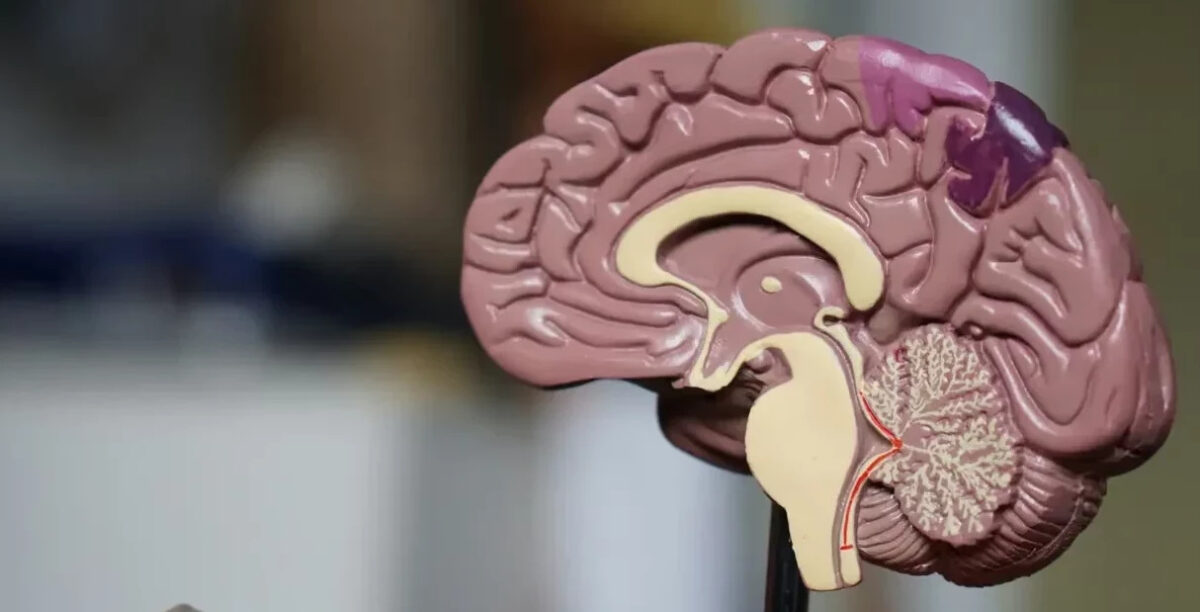

Over recent decades, neuroscience has achieved remarkable progress, yet the cerebellum, aptly named from the Latin for “little brain” and located at the brain’s rear, remains largely an enigma.

Despite holding three-quarters of the brain’s neurons in a near-crystalline structure, contrasting with the more chaotic neuron arrangement elsewhere, its complexity is not fully understood. While traditionally recognized for its role in controlling body movement, emerging research suggests this view is limited.

This expanded understanding of the cerebellum was highlighted at the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, DC, where neuroscientists convened to discuss its newly discovered functions beyond motor control. Innovative experimental methods reveal the cerebellum’s involvement in a range of activities, including complex behaviors, social interactions, aggression, working memory, learning, emotion, and more.

Historically, the link between the cerebellum and movement has been clear, evidenced by patients with cerebellar damage experiencing significant movement and balance challenges. Detailed studies have elucidated the cerebellum’s unique neural circuitry and its role in motor functions. However, a groundbreaking 1998 study in the journal Brain challenged this narrow perspective, detailing significant emotional and cognitive impairments in patients with cerebellar damage, suggesting its functions extend beyond physical coordination.

Despite these insights, the broader scientific community has been slow to acknowledge the cerebellum’s role in cognitive and emotional processes. Neurophysiologists like Diasynou Fioravante of UC Davis and neuroscientist Stephanie Rudolph of Albert Einstein College of Medicine have pointed out the longstanding observation of neuropsychiatric deficits in patients with cerebellar damage, yet a lack of anatomical evidence initially hindered the acceptance of these findings.

Currently, advancements in understanding the cerebellum’s circuitry are validating these clinical observations, challenging the conventional wisdom that limited its function to movement control, and opening new avenues for understanding its role in the brain’s broader cognitive and emotional landscape.