‘Bookstore’ Airbnb

Over 450 guests have stayed at “the world’s only bookshop Airbnb,” where they not only spend the night but also run the store during the day.

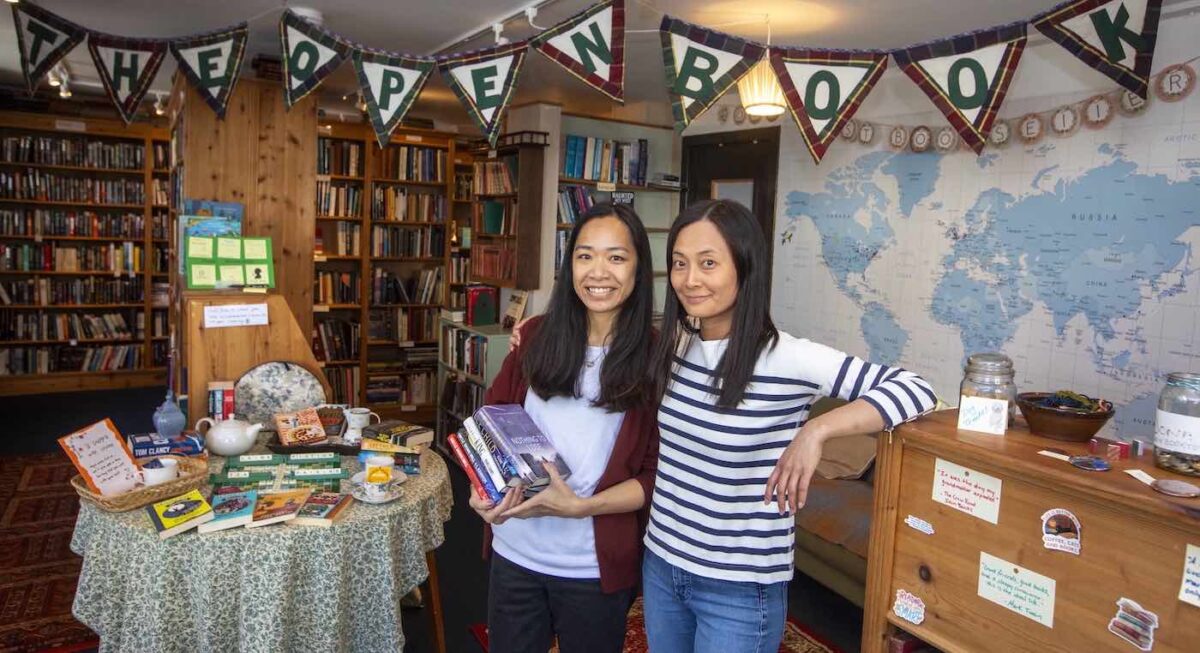

Located in Wigtown, Scotland’s National Book Town, The Open Book offers guests a chance to manage their own seaside bookshop. Airbnb calls it “the first ever bookshop residency experience,” and it’s so popular that the waiting list stretches two years, with visitors coming from as far as Hawaii and Beijing. The shop, established by The Wigtown Festival Company, aims to promote books, support independent bookshops, and welcome people from around the world.

Since opening in August 2014, The Open Book Airbnb has become a hit, with guests enjoying the unique opportunity to run the shop. One guest from Austin, Texas, told the BBC, “There’s no better feeling than somebody buying a book you put on display.” Airbnb describes the property as “a holiday home with a difference,” offering visitors the chance to run a real bookshop in Wigtown. Guests stay in the apartment upstairs and run the shop downstairs, with full freedom to change displays, price books, and get creative with the space. Some prefer a quiet approach, while others come with bold plans and ideas.