520-million Year Old Fossil Solves Mystery

A 520-million-year-old worm fossil has solved the mystery of how modern insects, spiders, and crabs evolved.

The fossil, named Youti yuanshi, dates back to the Cambrian period and offers a glimpse into one of the earliest ancestors of many species today. Its exceptional preservation, including the larva and its internal organs, makes it particularly noteworthy. Led by Durham University in the UK, the research team identified the fossil as one of the first arthropod ancestors belonging to the group euarthropoda, which includes modern insects, spiders, centipedes, and crustaceans. Their findings, published in the journal Nature, suggest that early arthropod relatives were more advanced than previously thought.

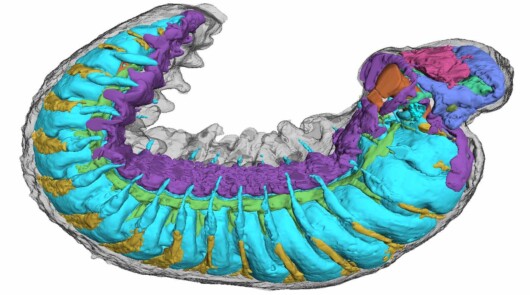

Dr. Martin Smith, Durham’s lead researcher, emphasized the rarity of such a discovery: “Finding a fossilized arthropod larva is almost impossible due to their tiny, fragile nature. When I saw the intricate structures preserved under its skin, I was astonished. How could these features avoid decay for half a billion years?” Using advanced scanning techniques at Diamond Light Source, the UK research team produced 3D images revealing miniature brain regions, digestive glands, a primitive circulatory system, and even traces of nerves in the larva’s legs and eyes. Dr. Katherine Dobson of the University of Strathclyde noted the near-perfect preservation achieved by natural fossilization.

This ancient larva offers crucial insights into the evolutionary steps from simple worm-like creatures to complex arthropods with specialized limbs, eyes, and brains. The fossil reveals an ancestral proto-cerebrum brain region, which would later develop into the segmented and specialized arthropod head with various appendages.

The complex head structure allowed arthropods to adopt diverse lifestyles and dominate the Cambrian oceans. The remarkable specimen was originally discovered in China and is housed at Yunnan University.