Van Gogh’s Starry Night: Scientifically Accurate

“Starry Night” is widely regarded as one of the most famous paintings in the world, second only to the Mona Lisa. But what many admirers might not realize is that van Gogh’s swirling sky is not just visually striking—it’s also “alive with real-world physics.”

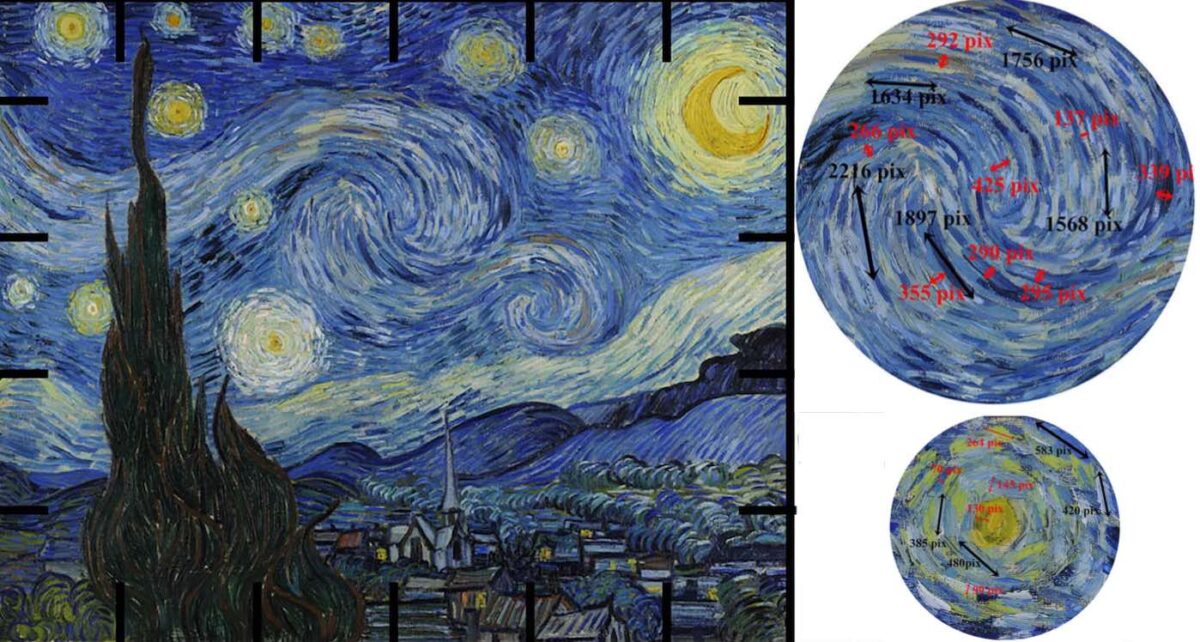

The brushstrokes in Starry Night create such a convincing illusion of atmospheric motion that scientists specializing in fluid dynamics in China and France became curious about how closely it mirrors the actual physics of the sky. Because you can’t measure actual motion in the painting itself, the scientists used van Gogh’s brushstrokes as a proxy for real atmospheric movement. By analyzing the scale and spacing of these swirling strokes, they found that van Gogh’s portrayal of the sky “accurately captures” energy cascading in turbulent flows—a phenomenon they call “hidden turbulence.”

According to Dr. Huang Yongxiang, one of the study’s authors, the size of the brush strokes was key. “By using high-resolution digital images, we were able to precisely measure the size of the strokes and compare them to turbulence theories.” The researchers likened the swirling brushstrokes to leaves caught in a whirlwind, which allowed them to analyze the shape, energy, and scaling of atmospheric characteristics in the painting. They also used the varying brightness of the paint as a stand-in for the kinetic energy of movement in the sky.

“It reveals a deep and intuitive understanding of natural phenomena,” Dr. Huang explained. “Van Gogh’s precise representation of turbulence might be from studying the movement of clouds and the atmosphere or an innate sense of how to capture the dynamism of the sky.” The study, published in Physics of Fluids, examined the 14 main swirling shapes in Starry Night and found they aligned with Kolmogorov’s law, a theory that describes how kinetic energy is transferred in turbulent flows from large to small scales.

On a finer level, the team found the brightness diffused in the brushstrokes also followed Batchelor’s scaling, which explains energy transfer in smaller, passive atmospheric turbulence. Finding both types of energy scaling in one system is rare, and it was a major motivation for their research.