11-Mile-Thick Diamond Layer in Mercury

A bi-disciplinary scientific study has identified a likely 11-mile-thick layer of diamonds at the boundary between Mercury’s core and mantle.

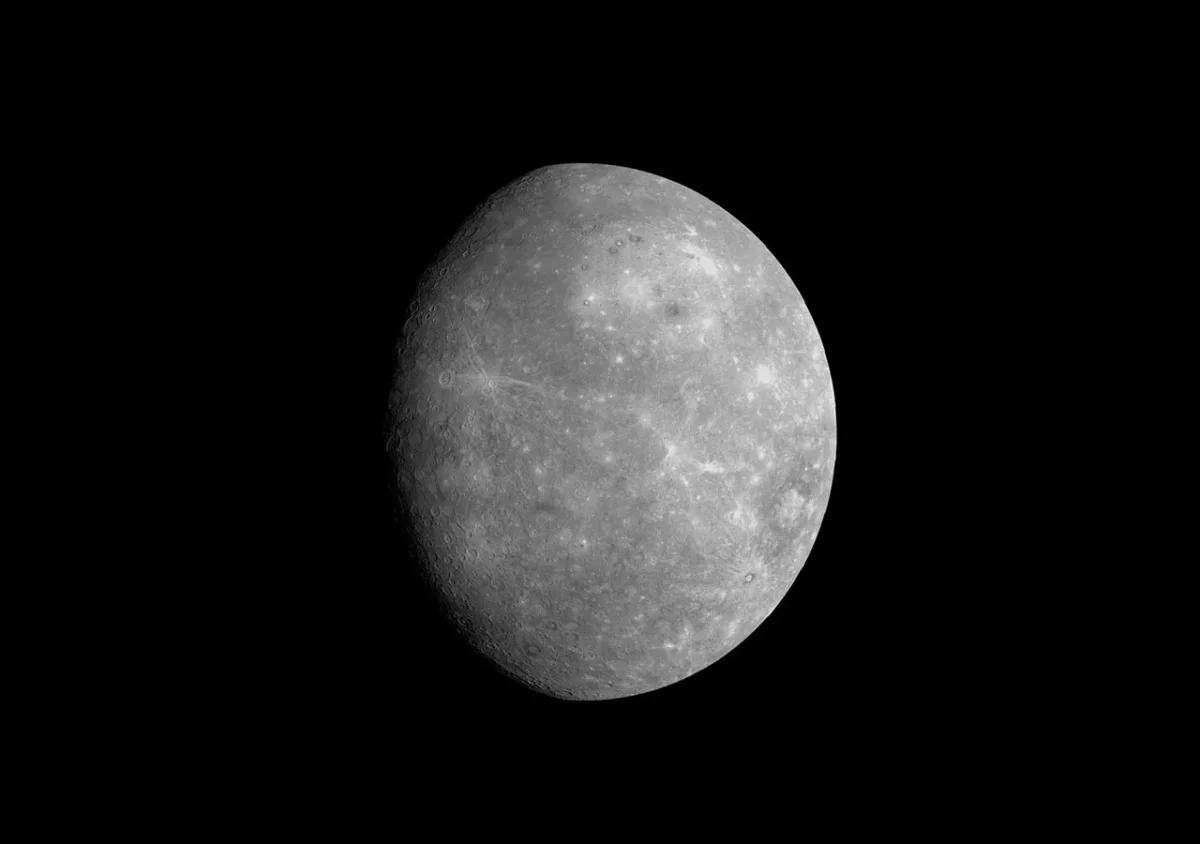

This finding is significant given that Mercury, despite being one of the closest planets to Earth, remains the least understood in our solar system.

Diamonds, which are pure carbon, are abundant throughout the solar system under the right conditions of pressure and temperature. Mercury’s surface, observed by the MESSENGER spacecraft from 2011 to 2015, appears grey due to its high graphite content. Graphite, another form of pure carbon, suggested to researchers that diamonds could be present below the surface.

“We know there’s a lot of carbon in the form of graphite on the surface of Mercury, but there are very few studies about the inside of the planet,” said Yanhao Lin, a staff scientist at the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research in Beijing and co-author of the study published in June in Nature Communications.

The researchers used a special pressure chamber to simulate conditions similar to those at Mercury’s core-mantle boundary—70,000 times Earth’s sea level pressure and 2,000°C (3,630°F). They mixed graphite with elements believed to be present in Mercury’s mantle, including silicon, titanium, magnesium, and aluminum. Under these conditions, the graphite transformed into diamond crystals.

By analyzing data from the MESSENGER mission on Mercury’s mineral composition and depth, the authors estimate the diamond layer is about 11 miles thick. However, mining these diamonds is not feasible due to their depth, similar to why Earth’s mantle cannot be mined.

“However, some lavas at the surface of Mercury have been formed by melting of the very deep mantle. It is reasonable to consider that this process is able to bring some diamonds to the surface, by analogy with what happens on Earth,” said Bernard Charlier, head of the department of geology at the University of Liège in Belgium and a coauthor of the study. While mining equipment would need to endure temperatures above 500°F, past asteroid mining achievements and plans from companies like Trans Astra suggest future possibilities.